Eating and drinking

It is common for conversations about dementia to focus on the neurological symptoms of the disease, like forgetfulness or changes in communication. But it is important to remember that while these changes are important and have a significant impact on people’s day to day lives, they are not the only symptoms and eating and drinking is often a topic of concern.

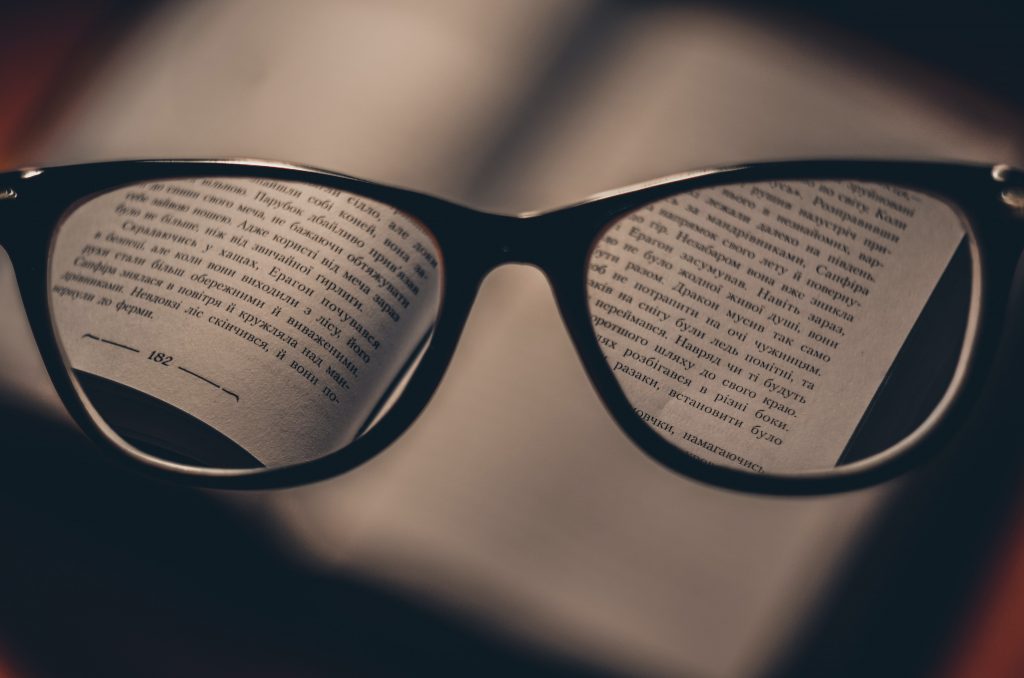

Our vision, smell, taste and hearing all play an important role in the eating and drinking experience. If a person with dementia has changes in the areas of their brain that help them make sense of what they see, they may find it difficult to recognise what is in front of them. If they don’t recognise the food in front of them, they may not be prompted to realise that they are hungry and that it is time to eat. Therefore we have to be mindful that visual and cognitive changes can make it difficult for someone with dementia when it comes to eating and drinking. You might find this leaflet on Dementia & Sensory Challenges helpful as well as Agnes Houson’s dementia diary.

The impact of changes in vision

- Consider increasing the brightness of light in areas where people eat or prepare food

- Natural light is best for seeing things in their true colour,

- If the area the individual eats in does not have good natural light levels, supplement it as necessary with artificial light.

- Contrasting the colour of the plate with the colour of the food being served can also support better nutrition and hydration.

- It can be difficult to see water in a glass because of the transparency, but by adding diluting juice may make it easier to see.

- A person with dementia may feel hungry and head for the kitchen but forget what they were looking for when they get there, without visual cues to entice someone to eat, the person may leave again without having anything.

- When stocking the kitchen, use the principle that “out of sight is out of mind” and place some nutritional food and drink options where they can be seen and prepared easily.

- Take some time to identify potential, healthy snacks and drinks that can be left visible in the kitchen.

The impact of changes in hearing

Many people with dementia talk about finding it difficult to filter out the extra noise in an environment. This can contribute to making it harder for someone with dementia to focus on eating. Extra noise can be distracting, frustrating, or frightening – especially when it happens suddenly or close by. This is why the DSDC suggests the person may benefit from eating in quieter restaurants, at a quieter time, or in a location that doesn’t include too much background noise

The impact of changes in taste

You may notice that someone with dementia often favours sweeter food over savoury or spicy options, which is likely due to how well they can taste those foods. This may influence the foods they choose to eat, as well as how they season their food as they increase the amount of salt (for example) to reach the same flavour that they are used to.

It is not unusual for an individual to begin to eat something they used to dislike or to stop eating something that was a favourite and it is important to remember that this is not always due to a ‘loss’ in ability or significant progression in someone’s dementia, but to a loss of taste sensitivity.

If a loved one is diabetic and they are drawn to foods with a high sugar content, have a conversation with the GP about the possible risks to the individual should they choose not to follow that diet

The impact of changes in smell

A person’s sense of smell is often one of the things that changes as their dementia progresses, often leading to a difficulty in identifying particular smells, or detecting odours at all. A loss in someone’s sense of smell can significantly impact how much, how often, or what they choose to eat or drink.

An example of recognisable smells could be coffee and toast in a morning.

Cooking and eating as a social activity

Though we eat and drink to survive, eating and drinking are also social activities. Food is often deeply ingrained in how we interact with others, whether that is going out for a meal or socialising with friends and family. It is this social element that can be missing for many older people who live alone in the community that can, in turn, mean that people eat less over time. Eating with others provides social cues that encourage regular nutritional intake.

Eating with others provides several advantages: first of all, it gives us a pleasant, meaningful activity that we can do while staying connected to the people that are important to us. Secondly, it serves as a prompt. For someone experiencing short-term memory loss, remembering to eat isn’t always easy. Eating with others provides social cues that encourage regular nutritional intake.

It is important to remember, that cooking can still be an important and meaningful activity for a person with dementia, when they are encouraged and provided with appropriate support. There are numerous assistive technology devices available to support independence in the kitchen for someone experiencing short-term memory loss.

It is worth checking to see what services may be available to you locally, if cooking becomes too burdensome, or is no longer of interest to the individual and is impacting on their health and well-being.

TIP: Written reminders

One common strategy used by people caring for someone with dementia who may forget to eat or drink is to use a whiteboard (or similar) placed somewhere they will see it often that they can refer to throughout the day. These might include ‘remember to drink water’ or ‘your lunch is on the counter’, for example.

TIP: Make snacks and drinks visible

Consider keeping healthy snacks like fruit visible to increase the chance that they will be picked up and eaten. Keep in mind special, favourite treats that can be left in strategic places to be enjoyed throughout the day.

Pain

Pain is a very common contributor to appetite loss and is also under recognised in people living with dementia. One particular acute problem which impacts on eating is poor dental care.

Depression

Many people with depression, both with and without dementia, will also experience a change in appetite where they begin to over or under eat. It is particularly important to keep this in mind as many people with dementia will also have depression,

Encouraging a healthy diet and hydration

Encouraging fruit juices is a good way to increase fluid intake and encourage vitamin consumption, though check with a GP as certain fruit juices may interact with medications. Cranberry juice is a particularly good choice as it has been shown to be effective in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections.

While most of us imagine sandwiches when we hear finger food, finger foods can include anything that is easy to eat by hand, and can include cheese, hard boiled eggs halved or quartered, fish fingers and meat slices to name but a few examples. Most fruits and vegetables can be presented in a way which promotes eating by hand, while snacks like crisps, nuts or even ice cream cones lend options to meal time.

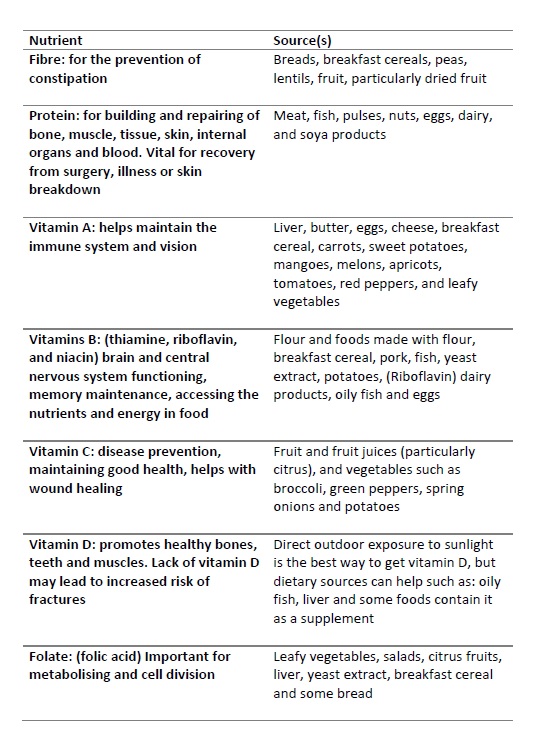

Nutrients to be encouraged:

Poor hydration affects mental function and can have a number of very serious consequences such as urinary tract infections, delirium, low blood pressure leading to dizziness and falls, constipation and kidney issues.

Warning signs of dehydration:

- Dryness of the mouth, lips and skin

- Sunken eyes

- Inelastic skin (if you gently pinch a bit of skin on the top of the hand and it does not return to its natural position quickly, this is an indicator of inelastic skin

- Drowsiness

- Increased confusion

- Low blood pressure

- Dark urine (urine should be light yellow to nearly colourless when properly hydrated)

- Foul smelling urine

If you suspect someone is deliberately limiting the amount that they drink, to prevent frequent visits to the toilet, or just don’t drink a lot, then the list of fruit and vegetables below which are high in water content may help in trying to combat hydration issues

Fruit and vegetables with a high water content:

Blueberries

Broccoli

Cauliflower

Celery

Cucumber

Green cabbage

Iceberg lettuce

Melon

Peaches

Pineapples

Strawberries

Raspberries

Tomatoes

Watermelon

10 top tips for improving nutrition and hydration

The following are our ten top tips for better nutrition and hydration for people living with dementia.

- Keep it in sight and turn on the light

It becomes important to use all of the tools at our disposal to support good nutrition and hydration. This begins with good lighting and placing or emphasising visual cues and clues which prompt the person with dementia to eat or drink. Leaving snacks and drinks for grazing throughout the day can be a help when short-term memory loss means someone gets distracted before completing the process of making a cup of tea. Having drinks available and visible at various places through the home will encourage spontaneous drinking. - Creating contrast

Sticking with the theme of keeping food and drinks visible, we can make both food and drinks more obvious by considering how they are served/presented. For example, consider serving light foods (like mashed potato) in a dark bowl or dish and vice versa. - Good smells and sweet starts

Use cooking smells to your advantage, as they will help to build appetite and keep eating and drinking at the front of the individual’s mind. If you are only there for short periods of time, consider which smells can be introduced quickly, like the smell of toast or the brewing of coffee. If the person complains that everything is tasteless and bland, try ‘sweet starts’. Sometimes starting with a small serving of pudding and then moving on to the main course can be helpful. - Make those calories count

If someone is struggling to maintain their weight, you can fortify the food they eat (provided their diet allows). Adding a bit of butter to cooked vegetables, using cream in place of milk, adding gravy to dishes, or custard to puddings are all good ways of increasing calorie content – but always consult a GP before starting to do so! - Getting a handle on hydration

It is important to remember, that hydration is not just about water, as the body will also draw water from other liquids and food during the course of digestion. It may be worth considering how you can encourage the individual to eat foods with a higher water content like soups, stews and even treats like ice cream, jellies, or ice lollies can contribute to a person’s fluid intake, so don’t be afraid to think creatively and consider all of your options when tackling hydration. - Exercise

For some people the onset of dementia may lead them to live a more sedentary lifestyle than they did in the past. This can have an impact on things like mobility, well being, level of cognitive stimulation, mental health and, importantly, their appetite. Getting regular exercise can support a healthy appetite and help to avoid issues with constipation. - Eating and drinking together

Eating and drinking is often a social activity. Eating alone might feel like one more task on the list of things that must be done today, whereas having a meal, a snack, or a cup of coffee with a friend is something to look forward to. So sit down and share a meal or drink together. If someone is having difficulty recognising their food or drink and knowing what to do with it, eating with someone else provides a visual example to follow which can encourage someone who might otherwise be confused about what to do. - Review medications

Medications are often needed to maintain good health, they can have a raft of side effects, some of which can impact a person’s eating and drinking. These can include nausea, constipation, dizziness, fatigue, and heartburn each of which can directly influence what, when, and how much someone feels capable of eating. Reviewing someone’s medication should be one of the first steps you take if you notice a significant change in their eating and drinking patterns. - A change of scenery

Everyone needs a change of scenery once in a while, and people living with dementia are no different. Perhaps a trip out for fish and chips, or a stop at the garden centre can often provide the stimulation (and meal options) to spark a waning appetite. - Try something new

Sometimes trying a new cuisine, adapting a recipe, or even something that a person, previously disliked can spark a new interest and prompt someone to eat. Successfully finding foods that someone who has lost interest in food will respond to can be a difficult task, and often requires lots of patience, trial and error. You may need to let go of your own expectations about what someone will and will not eat based on previous likes and dislikes.

Read more about eating and drinking for people with dementia in DSDC’s 10 Helpful Hints to Support Eating and Drinking for People with Dementia. If you live in Scotland you can request the 10 Helpful Hint series for free, thanks to funding.

Explore more…